Saint Lucie Child Pornography Lawyer Jonathan Jay Kirschner

On March 31, 2020 felony criminal charges pending against a wrongfully accused client were unconditionally ‘dropped’ by State prosecutors.

The prosecution resulted from an on-line investigation initiated by the Port St. Lucie Police Department (PSLPD) on the ‘BitTorrent’ Peer to Peer (P2P) file sharing network, attempting to ensnare offenders utilizing the network for sharing Child Pornography.

The PSLPD investigation took place over the course of three (3) months, and on May 8, 2019 resulted in the Defendant’s arrest in State of Florida vs. VHD, St. Lucie County case 56-2019-CF-001261-A.

In addition to the indignity and humiliation of being arrested, VHD was saddled with a fifty-thousand dollar ($50,000.00) bond. Fortunately, he was able to bond out of jail, which enabled him to assist in his own defense, as well as to maintain a semblance of normalcy in his life pending resolution of the case.

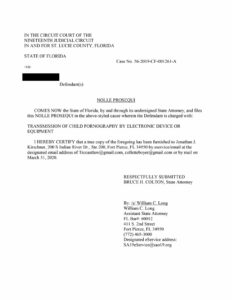

Upon review by the State Attorney’s Office for the 19th Judicial Circuit, a formal charge of violating section 847.0137, Fla. Stat. [Transmission of Child Pornography by an electronic device] was filed on May 23, 2019. The charge is a 3rd degree felony in Florida, and if VHD was convicted, could subject him to a five (5) year prison sentence.

A copy of the formal charging instrument, called an “Information,” appears below:

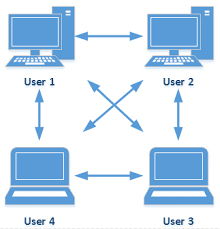

“P2P” systems have been available since 1999-2000. These systems consist of a distributed application that partitions tasks or workloads between “peers,” i.e., to other users to whom the application has been distributed. Peers are equally privileged, equally potent participants in the application.

Peers make a portion of their resources, such as processing power, disk storage or network bandwidth, directly available to other network participants, without the need for central coordination by servers or hosts. Peers are both suppliers and consumers of resources, in contrast to the traditional ‘client-server’ models, in which the consumption and supply of resources is divided.

Simply stated, in traditional centralized downloading, there exists a central web-server, from which multiple downstream users seek to download data. Such traditional systems suffer from being slower, having a single point-of-failure, and can burden the centralized server with substantial bandwidth requirements.

P2P systems however, because all downloaders also are uploaders, are much faster and have no single point-of-failure. A flow chart of data in a typical P2P system appears in diagram #1 below:

For those unfamiliar with such systems, one of the earliest iterations was “Napster.” Others include “Gnutella,” “Limewire,” “E-mule,” “Kazaa,” “WinMX,” and the like. These systems typically are used in popular culture to download and ‘share’ music, movies, and other data compilations that require larger amounts of bandwidth. [1]

Unfortunately, these file sharing systems also have been utilized for the sharing or ‘trading’ of inappropriate and illegal materials like ‘child pornography’ (CP), and consequently have become the focus of many law enforcement efforts; local, State and Federal.

Law enforcement agencies rapidly concluded that P2P systems, since they are voluntarily downloaded by end-point users, could also be ‘voluntarily’ downloaded by the agencies themselves, and as such they developed the technological means to identify all of the internet service providers (ISP’s) who were linked to various P2P systems. Once those forensic software solutions were developed, those agencies began infiltrating those systems/networks, in an attempt to identify users utilizing P2P systems for illegal purposes.

Many law enforcement agencies can readily identify the ISP addresses of any and all users of these systems within almost any identifiable geographical area. Then, by contacting the ISP providers themselves, they are able (through the use of investigative subpoenas, and occasionally even less formal investigative techniques) to obtain the names and addresses of the users of P2P networks.

These agencies also have the ability (through the use of databases of inappropriate/illegal materials that have been assembled over decades of law enforcement investigations and subsequent prosecutions) to identify illegal data files, i.e., photographs, movies, etc., via ‘file names’ [which can easily be altered, but oftentimes are not] and ‘hash tags,’ which cannot be readily altered.

Then, by simply becoming voluntary users of a particular P2P network, and in conjunction with the use of proprietary forensic software, law enforcement officers operating in an undercover capacity now are readily able to identify the names and addresses of P2P network members possessing and disseminating inappropriate or illegal data to other P2P network user/members. This data may include possessing, collecting or trading files ranging from simple copyright violations of musical performances, to traders and traffickers in pornography, government secrets, and anything else deemed to be a violation of local, State or Federal laws.

The courts however, have circumscribed what otherwise might have become a law enforcement ‘free-for-all’ in terms of violating the privacy rights of innocent users of P2P technologies.

The basis for the judiciary’s interference in these systems is the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Our courts have determined that law enforcement agents may not, merely because they are members of the same P2P network, simply enter into another member’s computer, and execute searches of the user’s ‘shared files’ in those machines, in order to form the basis of a criminal prosecution.

In this case—that is precisely the tactic adopted by PSLPD in instituting the investigation against VHD.

The basis of the claimed Fourth Amendment violation here was that the search warrant obtained by the PSLPD was not legally obtained, despite the fact that the gendarmes who obtained the warrant actually named the registered user of the ISP, and thus drawing the connection between the user and the internet.

The key in this instance is the fact that the PSLPD was not able to ‘connect’ the registered ISP customer as the sole person who had access to the computer that forwarded the objectionable material.

In order to use the seized materials that were transferred from the machine located at the suspect’s ISP address to the law enforcement undercover operatives, PSLPD was first required to demonstrate to the issuing Judge that the undercover agent had been “invited” to enter the ISP customer’s computer in order to access the P2P files from which the objectionable material allegedly had been derived.

The investigative plan developed by PSLPD was legally insufficient to permit the judge who issued the warrant to have ‘signed off’ on the warrant application, and thus PSLPD had failed to establish the requisite ‘probable cause’ upon which to base a decision to issue the warrant in the first instance.

Upon analyzing the facts obtained from the government’s documentation, as supplemented by sworn deposition testimony from the PSLPD law enforcement agents, JJK & Associates, LLC., was able to construct a legally sufficient verified motion to dismiss the case utilizing a rarely summoned criminal procedural rule. A copy of that motion is reproduced below:

[gdlr_row]

[gdlr_column size=”1/4″] [/gdlr_column]

[/gdlr_column]

[gdlr_column size=”1/4″] [/gdlr_column]

[/gdlr_column]

[gdlr_column size=”1/4″] [/gdlr_column]

[/gdlr_column]

[gdlr_column size=”1/4″] [/gdlr_column]

[/gdlr_column]

[/gdlr_row]

[gdlr_row]

[gdlr_column size=”1/4″] [/gdlr_column]

[/gdlr_column]

[gdlr_column size=”1/4″] [/gdlr_column]

[/gdlr_column]

[gdlr_column size=”1/4″] [/gdlr_column]

[/gdlr_column]

[gdlr_column size=”1/4″][/gdlr_column]

[/gdlr_row]

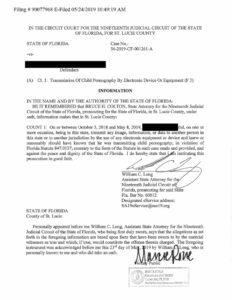

The motion was set for a hearing before the trial judge on April 24th, 2020. After reviewing the motion, the prosecutor assigned to prosecute our client made the legally sound decision of dismissing the action in its entirety, and the dismissal was filed on March 30th 2020. A copy of the dismissal appears below:

Hiring a Saint Lucie Child Pornography Lawyer

Although VHD will never recover the money, time and aggravation lost in defending this unnecessary, unwarranted, and legally flawed action, — the entire prosecution is forever dismissed, and the unwarranted and legally improper exercise of police power by PSLPD stands defeated….not solely as to VHD, but hopefully for others who are similarly situated and risk being victimized by law enforcement overreaching.

In the legal profession, this is what we call a “win.”

[1] The tendency of P2P file sharing systems to be utilized by some users in order to gain access to copyrighted material has led to substantial litigation over the intellectual property rights of the producers of the films, music, etc., that is shared at no cost between users of these systems. (Criminal prosecutions premised upon that ‘illegal’ usage is not uncommon, and will be addressed in different posts on this site).

[2] And in this instance, the registered user of the ISP was not the Defendant here.